Reflections on Community Health Nursing in Shomron (2002-2023), with sources from the academic literature

Reflections on Community Health Nursing in Shomron (2002-2023)

Introduction

The following are insights into the role of culturally competent care, trust-building, personal contact, and evidence-based practice in public health. Throughout my tenure as a community health nurse in Shomron from 2002 to 2023 , I observed the importance of trust-building on a local level, the positive effects of collaborative management in which nurses were included in decisions, and the damage that the a paternalistic management style does to healthcare delivery.

This essay explores these themes and the positive impact of culturally competent nursing on vaccination compliance (Schim, Doorenbos, Benkert, & Miller, 2007) and the role of religious nurses in healthcare systems (Héliot et al., 2019).

The Role of Trust and Culturally Competent Care in Public Health

Imanuel is a largely haredi (ultra-orthodox) community, founded in the late 1980's. It is unique in that it has never experienced an outbreak of a vaccine-preventable contagious illness. This success, I believe, was largely due to proactive community engagement, a crucial element in effective public health practice (Schim et al., 2007). The school nurse who preceded me was a haredi woman who lived in Imanuel and consistently reached out to parents in person at chance meetings in part, shop and synagogue to encourage vaccine compliance.

After she moved away, I followed her lead.

I organized extra vaccination days in Imanuel and nearby Kedumim. By living here and forming relationships with community members, I was able to encourage partial vaccination compliance even among families initially opposed to vaccines. Some of these families have several children and large extended families throughout Israel. This means that such trust-building may have had a ripple effect in other areas of Israel, among families who had previously refused vaccination.

Because the lack of access to social and electronic media among haredim, most of the population in Imanuel needs the school nurse to be present more frequently. I would enter schools on my own time in order to hand out vaccine notices in order to increase compliance. As a local resident, I integrated health discussions into daily interactions.

Any rumor that haredi orthodox Jews do not vaccinate is simply untrue. Research supports that building trust with populations leads to higher compliance and better health outcomes (Schim et al., 2007; Fu, 2024).

Many parents who were initially hesitant about vaccines eventually agreed to partial vaccination due to personal trust in me as a community member and healthcare professional. This aligns with evidence-based nursing practice, which emphasizes direct communication in improving health behaviors (American Nurses Association, 2024).

Growth Evaluations

Height and weight evaluations are critical in child development, and in 2002, were performed in grades 1,3,5, and 7. From about 2005, growth evaluations would only be performed in grades 1 and 7.

We told our management, and I spoke up at a meeting in which representatives from the Ministry of Health were present, that the seventh grade is often too late to fix a growth problem, appointments with endocrinologists are often many months in the future, I publicly requested that we should at least perform growth evaluation in the fourth or fifth grades, but our pleas fell on deaf ears.

Parents are not always aware, caring, or available. Intervening with a growth abnormality at a young age can be crucial, it may reflect a deeper underlying health problem, even a future fertility issue, and in some cases can actually be life-saving.

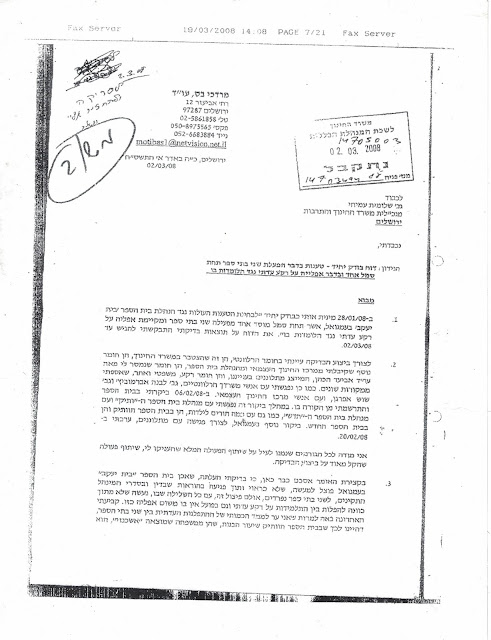

You may refer to the letter of thanks from one mother whom I encouraged, over the years, to take her daughter to an endocrinologist due to her short stature. This compliance would not have happened via cold calls and rare encounters.

The Unique Contribution of Religious Nurses

Religious nurses bring a unique set of values and ethical commitments to healthcare settings. Studies indicate that religious identity can enhance workplace contributions when there is alignment between occupational and religious values (Héliot et al., 2019). I viewed my work as spiritually significant, indeed, one haredi rabbi told me, "Every vaccine you give is an enormous mitzvah."

When I shared this quote with the head nurse, who had been head nurse in this organization since about 2015, she flicked her hand dismissively, made a scornful facial expression, and said, "think what you want."

Thus, my commitment was not recognized by upper management.

This head nurse exhibited open contempt toward me when I asked a colleague about the kashrut of snacks that were offered at a gathering. This question was not directed at her nor was it intended for her.

My commitment to keeping kosher dovetails with my commitment to nursing as spiritually significant.

The head nurse's contemptuous attitude towards me on religious grounds felt like harassment. This contradicts the research that shows that accepting religious workers improves their job performance (Héliot et al., 2019).The Shift from Community-Based to Task-Oriented Nursing

Initially, I worked weekly at two schools, allowing me to monitor post-vaccination effects. Beginning in approximately 2005, school nurses received a larger work load and were not present regularly at schools. School nurses were instructed to tell teachers to report vaccine side effects, despite teachers being overwhelmed with other responsibilities, and really not trained; additionally, epidemiology changes, perhaps new side effects are being expressed that nurses should note?

This shift represents a decline in the role of school nurses as trusted health professionals within the school system (Schim et al., 2007).

Furthermore, workload expectations increased drastically. Under various administrations—Aguda, then Natali—nurses were initially expected to perform 30 vaccines per day, a reasonable goal. However, under that organization's management, which began about 2012, this increased to 40-50 vaccines per day, placing immense psychological pressure on nurses. The 2022 lawsuit against that organization, where a child in a school in Petach Tikva was mistakenly given a double dose of the Tetanus-Diphtheria-Pertussis vaccine within a week, highlights the dangers of prioritizing quantity over quality in healthcare (American Nurses Association, 2024).

Only after this lawsuit did the management decrease the demand for high volume.

The Accessibility Crisis in Vaccination Services

Another significant issue was the limitation of vaccine availability. Until 2005, vaccines for school-age children were available at both schools and public health clinics. However, after a policy change, vaccines for school-age children were only administered in schools, limiting access for parents who could not attend scheduled school vaccination days. Clinics offer flexible hours, including afternoon and Friday appointments, which are more convenient for working parents (Schim et al., 2007). School nurses only administer vaccines from Sunday through Thursday, only from 8am to 2pm.

If the goal of public health policy is high vaccine coverage, why restrict vaccine availability? Schools only offer vaccinations sporadically, whereas clinics operate regularly and have evening and Friday morning hours. School nurses are much less in acquaintance with the parents than the local health clinic nurse, as school nurses appear in schools only sporadically.

The lack of flexibility forces parents into inconvenient options, reducing compliance and defeating the goal of widespread immunization (Schim et al., 2007).

Culturally Congruent Care and Public Health Success

Outbreaks of measles, polio, whooping cough, and chickenpox have been recorded across Israel. However, Imanuel has remained outbreak-free. One key factor was understanding the cultural behaviors of the population. Knowing that families travel extensively during the High Holidays, I prioritized early vaccinations at the start of the academic year. This proactive approach ensured that children were immunized before traveling, a practice supported by culturally congruent care models (Schim et al., 2007). This is an example of culturally competent nursing, which aligns with research on the importance of cultural sensitivity in healthcare delivery (Schim et al., 2007). If vaccination timing is a crucial factor in community health, why isn’t it prioritized in national public health planning?

Management’s Resistance to Feedback and Evidence-Based Practice

A key issue within that organization’s administration was the absence of a feedback loop between field nurses and policymakers. Nurses were expected to follow procedures without questioning their effectiveness. When nurses voiced concerns—such as unrealistic vaccine quotas or the lack of informed parental consent—they were ignored or reprimanded.

For example, since 2016, parental consent for vaccinations in Israel has been based on a signed health declaration at the beginning of the school year. This policy assumes that parents are fully aware that their signature grants blanket consent for all vaccinations. In reality, many parents do not understand this policy. When nurses raised concerns about this, they were instructed to proceed with vaccinations regardless of parental misunderstandings. This approach is not aligned with ethical nursing practice, which prioritizes informed consent.

The Psychological Toll on Nurses

The lack of autonomy and punitive management style created a culture of fear among nurses. Many nurses resorted to calling parents in secret to verify their wishes, despite being officially prohibited from doing so. Others left school nursing, having been pressured by this management to refrain from phoning the parents to assess their true wishes; these nurses were unwilling to vaccinate children without explicit parental confirmation.

Additionally, workload pressures led to burnout. Nurses were forced to order excessive vaccine quantities to meet unrealistic quotas, knowing they would return unused doses at the end of the day. This created a deceptive work culture where nurses had to manipulate numbers to meet expectations, instead of focusing on providing quality care.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Healthcare is built on trust—between nurses and their communities, and between management and their staff. To improve public health outcomes, the following steps should be taken:Reintroduce a community-centered approach to school nursing, ensuring that nurses have time for relationship-building and patient education (Schim et al., 2007).

Revise vaccine availability policies to allow both schools and clinics to administer vaccines, making immunization more accessible.

Implement feedback mechanisms that allow nurses to communicate field experiences to policymakers, ensuring that directives are aligned with real-world healthcare challenges (Héliot et al., 2019).

Shift from a hierarchical management style to a collaborative one, empowering nurses to use their professional judgment (Héliot et al., 2019).

Reassess the policy on parental consent for vaccinations, ensuring that parents fully understand the implications of their signed health declaration.

The true measure of successful community health nursing is not just in metrics and quotas, but in trust, accessibility, and ethical practice.

Many thanks for the opportunity to serve.

Comments

Post a Comment